Where there’s smoke…there’s lost productivity

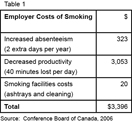

| It may surprise you to learn that Canadian tobacco manufacturers sold an astounding 17.5 billion cigarettes in 2008, according to Statistics Canada. Even though Canada has one of the lowest rates of adult smoking in the world, it is clear there is still a long way to go to before tobacco does no harm. Almost one in 5 Canadians aged 15 or older continue to smoke. On average, those who smoke daily consume about 15 cigarettes each day, or almost 5,500 cigarettes annually. There is good news though: · The sharpest declines in smoking, as measured by the 2005 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), were among youth aged 12 to 17. The rate decreased from 14% in 2000-01, to 10% in 2003, and to 8% in 2005. Over eight in 10 youth now say they have never tried smoking. Smoking usually begins before age 18, so further declines in the adult smoking rate are likely. · In 2005, 68% of the employed population reported workplace smoking bans, up from 62% in the 2000-01 CCHS. That figure should already be significantly higher, since workplace smoking bans only appeared in Ontario in 2006, and in Quebec and Alberta in 2008. · Smoking policies at work (or at home) reduce consumption. Smokers who had total smoking bans at work smoked an average of 11 cigarettes daily, compared with 14 for those who could smoke at work. For people forbidden to smoke at home and at work, the number dropped to 9 cigarettes per day, on average, versus 16 for those who could smoke at home and at work. · Eight provinces have now enacted complete prohibitions on smoking in public places. British Columbia and Prince Edward Island allow only partial bans. Ironically, BC wants to bill itself as the healthiest province in Canada, and PEI has the nation’s highest rate of lung cancer. These are important figures for Canadian society, since we collectively pay the price for tobacco consumption. But these trends also matter to employers. Why Address Tobacco? The Conference Board of Canada compiled data in 1997 and in 2006 to estimate the cost of a smoker to an employer. The original cost was $2,565; by 2006 it had increased 32% to almost $3,400 (see Table 1). That increase was mostly due to a higher average daily wage. Since Statistics Canada now reports that daily figure has increased a further 20% from what the Conference Board used, the 2006 cost estimate to employers is undoubtedly conservative. Organizations also suffer other indirect costs to smoking. Corporate reputation may be negatively impacted by smokers and smoke lingering outside building entrances. Apart from the productivity losses noted above, smokers can also create friction among staff because their recurrent need for smoking breaks may cause others to believe they are less committed to their job and their behaviour interferes with team-based work. In 2003, the Ontario Medical Association estimated a productivity cost of smoking in that province of $2.6 billion. In some provinces, second-hand smoke may create an unsafe work environment, whether in a commercial building or other structure. For example, the Smoke-Free Ontario Act prohibits smoking in an “enclosed workplace” that includes a vehicle with a roof and that employees work in and frequent. Employees may also refuse to work in a home where the resident refuses to extinguish a cigarette. Employers should get appropriate legal advice about the work situations faced by To complement provincial smoking bans and even the “rules” smoking employees face at home that restrict where and when they can smoke, workplace policies are still needed to change smoking behaviours. In a study of smokers who initially reported no smoking restrictions at work, Statistics Canada found that two years after implementing a complete ban on workplace smoking, twice as many (27% vs. 13%) smokers had quit, compared to smokers who continued to have no restriction on smoking at work. As reported previously (see e-news 3:3, Pushing the Envelope, July 2007, available at www.businesshealth.ca), some American employers will not employ smokers. Others require their smoking employees to quit by a certain date, subject to termination. Supportive policies need to be in place for such hard-line approaches, and legal advice should be sought before implementing The battle to stop smoking is a long one, fraught with many attempts and much frustration. Though quitting is a personal decision, employer policies and health benefit programs have an important role to play. Sources: Berman, M., Crane, R, 2008. Mandating a tobacco-free workforce: a convergence of business and public health interests. William Mitchell Law Review 34(4): 1651-1674. Conference Board of Canada, 2006. Smoking and the bottom line: updating the costs of smoking in the workplace. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada. Fichtenberg, C., Glantz, S, 2002. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systematic review. BMJ 325:188-191. Maltby, L., 2008. Whose life is it anyway? Employer control of off-duty smoking and individual autonomy. William Mitchell Law Review 34(4): 1639-1649. Statistics Canada, 2007. Study: Smoking bans: Influence on smoking prevalence. The Daily, August 27. |