Things you need to know about ADHD

ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) is a common condition associated with broad functional impairment among both children and adults and can have a negative impact on both family and work life. In our Doctor on Call feature on the next page, Dr Kenny Handelman discusses the direct impact of adult ADHD on the workplace. Discussion here focuses on the indirect costs of ADHD on employees and organizations in two situations – when an employee does not have ADHD but has a family member with ADHD and when ADHD occurs with another psychiatric condition.

WHEN ADHD IS IN THE FAMILY

Workplace costs rise even when a family member, not an employee, has ADHD. Researchers1 have found that both children and adults with ADHD have higher annual medical costs, and that indirect costs in the workplace related to disability and absenteeism are higher for employees with family members with ADHD. Reasons for the higher indirect costs include: parents use energy and attention caring for their children, are often required to miss work to meet with teachers or take their children to appointments, and are coping with the economic burden of their child’s condition, including effects on their own employment patterns or career chances (e.g. leaving work to attend to a child).

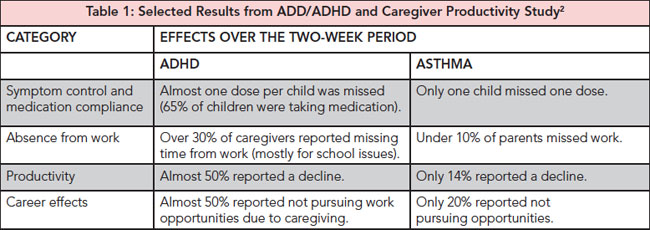

A Canadian study of caregivers of children with ADHD2 confirmed that having ADHD in the family impacts health and productivity (tangible measures of health include the costs of drugs, employee assistance, and all absences, including long term disability). The study explored the effects on caregiver productivity of having a school-age child with either ADHD or asthma using a self-reporting survey administered for a two week period. Questions were organized into four categories. Sample results from caregivers of 272 children show that caring for a child with ADHD is associated with greater negative impacts than caring for a child with asthma (Table 1). Researchers note that the “majority” of compliance issues revolved around “daytime administration of ADD/ADHD medication where there is no parental control or supervision.” (Asthma medication is taken only in the morning and at night.) They suggest that compliance could be improved with administration of medication in a “once-per-day” form, an issue discussed further by Dr Handelman on the following page.

WHEN THERE ARE COMORBIDITIES

ADHD can also have an indirect effect on workplace costs when it is “hidden” as a comorbid condition. Individuals with ADHD tend to have higher rates of other co-occuring conditions, including anxiety, depression, substance abuse and learning disabilities.3 Approximately 87% of ADHD children have at least one comorbid condition and 67% have at least two. Researchers believe that 77% of ADHD adults meet criteria for a comorbid condition and suggest that comorbidity contributes to the failure to diagnose ADHD in adults. Comorbidities increase the complexity of ADHD, an already complex condition, and make workplace efforts to support employees more complicated.

WHAT TO DO?

Clearly, education is needed to increase awareness of ADHD and its potential direct and indirect impacts in the workplace. Efforts are needed to ensure that individuals with ADHD or ADHD in the family are identified and receive appropriate accommodations and interventions. Even when treatments increase costs, they are likely to be wise investments that will ultimately result in better outcomes for individuals and the organization.

Notes:

- Matza, L. S., Paramore, C. & Prasad, M. 2005. A review of the economic burden of ADHD. Cost Effectivenss and Resource Allocation, 3(5). E-version accessed 6 June 2013 at http://www.resource-allocation.com/content/3/1/5

- Dick, E. & Balch, D. October, 2004. ADD/ADHD and Caregiver Productivity, Benefits and Pensions Monitor Online. Accessed 10 June 2013 from http://www.bpmmagazine.com/02_archives/2004/october/add_adhd_caregiver.html

- Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA). March 2013. Chapter 2: Differential Diagnosis and Comorbid Disorders. CADDRA Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines, 3rd Ed., p. 3. Markham, ON: Author.